Kingdom of Motapa and Beyond

Have tools will travel

Between 1430 and 1760, there existed a great kingdom in Sothern African, Monomotapa, known as the Mutapa Empire, which was ruled by the Shona people. This kingdom of Mutapa incorporated what we know today as Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, including Swaziland and Lesotho, as well as parts of Zambia.

Because of the huge armies, the kings ruled and taxed – demanding tribute as in Roman times – from areas beyond their immediate borders, incorporating them into the structure of their vast kingdom. The Mutapa influence stretched from the Zambezi River to both the coasts of the Indian and Atlantic oceans and down as far as Cape Point.

The Shona, being a Bantu people, were not known as hunter-gatherers or pastoralists but as industrialists and farmers, including pasture with hunting. This is born out by their cities, mining and tools, having descended from the builders of the Great Zimbabwe.

The monarchy developed a system of statehood with a strong monotheistic religious structure and was not only advanced but well organized, even welcoming western advisors. Because of their knowledge in working metal – gold, steel, copper and iron – they had the tools to maintain a high order of civilization. Farming, mining and exports went to distant parts of the world.

The Mutapa traded with Arabia, Persia and India including leopard skins, tortoise-shells, ivory, horn, gold and copper, with many of these already fashioned into artifacts, sent from their ports – mainly Sofala – for shipment elsewhere in the Indian Ocean.

The ability to work iron was an enormous asset for farming, fishing, mining, woodworking, boat making and endless crafts, which remain with these people to this day. The influence of these iron-makers made them – and most of the southern regions of Africa – a prosperous group of nations within themselves. These isolated nations have the tool-making ability to thank for their successful expansion over a period of some 4,000 years.

The seeming utopia that existed in Monomotapa was shattered by the arrival of the Portuguese in the 16th century and infighting among themselves, which brought this mighty kingdom to an end after a rule of over 300 years but not without leaving a rich heritage for the entire Southern African region.

Having searched most of Africa, the Portuguese first conquered the Mozambique territory with the aim to claim the great Monomotapa wealth that existed in this region, to export to Portugal. This action came about because of their unsuccessful occupation of South America – their El Dorado. Consequently, they needed Southern Africa’s riches for export to Europe.

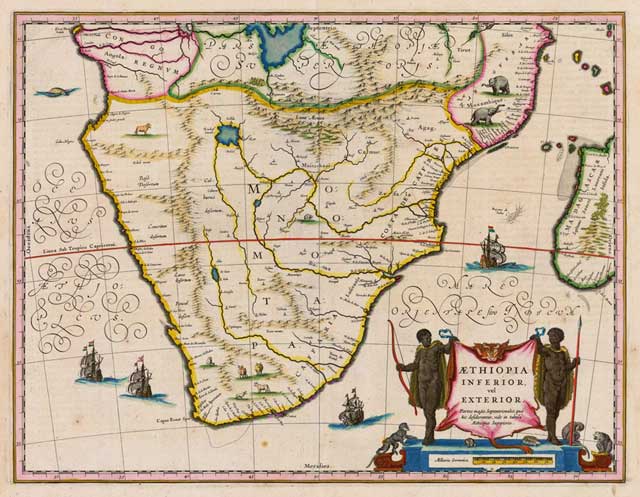

A map made by the Portuguese of the southern region of Africa.

The pitting in these artifacts proves there was a high carbon content in the metal blades – a good thing.

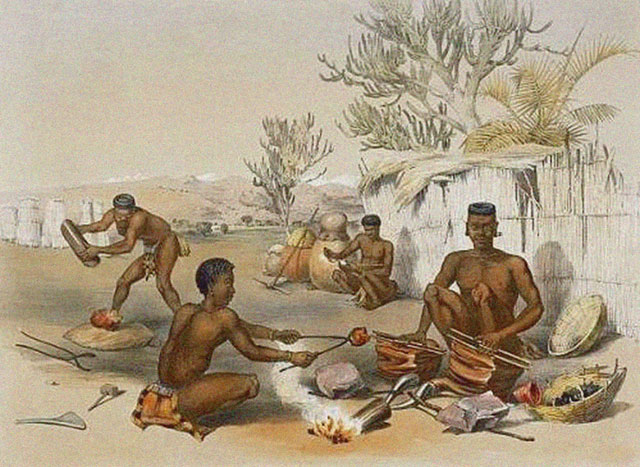

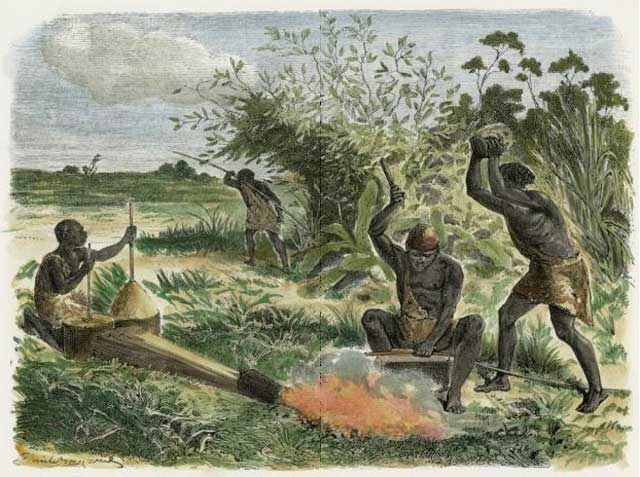

A fortuitous visit to a recreated Shangaan village in the south of Zimbabwe at Malilangwe, demonstrates how the people made iron tools, implements and weapons of war. Here are some images demonstrating the methods used to work iron on a rudimentary basis.

The bellows also provide the necessary oxygen needed for a better heating of the coke oven.

Coking coal and charcoal are essential for even heat and necessary to removing impurities in the metal being heated by raising the much-needed carbon levels for hard steel. At this stage, oxygen is not applied to keep the carbon levels high in the oven while treating the iron/steel to obtain the best quality.

This is the all-important stage to get the metal the right temperature at around 1000-1100ºC. In case you don’t know, this is done by observing the colour of the metal. A well-versed metallurgist is trained to know this colour by heart and therefore knows the heat range by sight.

Here the metal is folded and beaten like working clay or plasticine until the desired results are reached. Sharp-edged tools require a high degree of carbon, with the shaft having a lower degree to keep the elastic of the shaft – tang – to prevent snapping off. Many processes like quenching in oil or water are also applied and this article is not a definitive work on tool making. The technical data supplied here is by the writer, not the iron maker.

It might be well worth mentioning, at this time Europe was still emerging from the decadent Middle Ages and England and France were embroiled in the futile 100 years war, between the Plantagenet’s, rulers of England and the Valois, rulers of France.