Selati Line – Part IV

Selati Line – Part 4

During the Anglo-Boer War

Some People Have Been Brought Back to Life

As mentioned in our last story, we are redressing the death stats of our Selati Line. There are some reliable figures for railway construction deaths in the late 1800’s and as is stated here, 13% of the labour force, including those from around the world who came to work on the Eastern Line for the Netherlands South African Railway Company (NZASM) died of fever or work related incidents, according to a report given by them in 1894. No mention was made of predator attacks, – like lion – so it may not have occurred. Of course, this railway line stretched from Komatipoort to Pretoria, having gone along the Crocodile River, through the Drakensburg, past the lower side of Nelspruit, up the Crocodile valley, to the Elands River valley and on up to Waterval Boven, past Middleburg and ending at Pretoria. This lower area had a lot of fever and plenty lion in general but not in the numbers of the Selati Line. And these lion were less likely to make an attack on units so close to civilization.

Obviously, the area between the Crocodile and Sabi Rivers, along the Selati Line, was far more exposed and treacherous owing to all the abundant game and the remoteness of the predators, so let’s double that figure given by the NZASM, to 26%. If there were 10,000 workers on that line, it would be 2,600 deaths and that’s a far cry from 80,000 lives. But you be the judge, though 2,600 is more than enough for the lions to eat, or to bury in little over a year, on one 80 km (50 mile) railway line.

There’s a Snake in the Grass Here Somewhere

Seven years later, abandoned, forgotten, but not gone forever, our Selati Line finds uses in spares and military action. Spares, in that during the Second Anglo-Boer War, a stratagem is derived upon by the British High Command, to interrupt trains between Pretoria and Delagoa Bayto by blow up a bridge, any bridge. At first, the bridge at Komatipoort was considered, this idea was quickly abandoned, due to high security there. Malelane became the next obvious choice, since that was the closest other bridge to the border and more easily reachable.

This mission was to be undertaken by the British Guerrilla Secret Service corps of Steinaecker’s Horse under the intelligence arm of the Natal Commander Gen R H Buller. Known by the code name of ’S & Co’. (Steimaecker & Company). This was Lt. Baron Christiaan Ludwig Franz von Steinaecker and his detachment of horseman – as discovered in his secret service records. A German born in Berlin (1854-1917), who came from Prussia to South West Africa then on to Natal, there becoming a British subject on 29 June 1897 and known as Francis, was appointed senior officer to this cavalry outfit. Steinaecker had, at that time, made his main camp in the Lebombo Range, at a place known as Nomahasha – to some Lomahasha – on the southeastern Swaziland border. Note, Swaziland was an imperial, friendly and neutral country at the time and no hostile forces should have been there.

Leaving for Malelane one – supposed – dark night from Nomahasha on horseback, von Steinaecker, accompanied by J B Holgate and one pack horse with 50 kg (110 lbs) of dynamite, also fuses and detonators, arrived at the Malelane Bridge on Saturday, 16 June 1900. The following morning, the two men took an hour to set up the explosives that destroyed the 80 foot high bridge, an adjacent pumping station and cut a large section of telegraph wires. That night, the two men rode back the 140 km (80 miles) to Nomahasha, mission accomplished.

Fortunately, the NZASM, who owned and operated the railway from Pretoria to Delagoa Bay, could commandeer long heavy timbers from – you guessed it – the abandoned Selati Railway, to repair their line. Into the picture come two Italian brothers. Giacomo and Guiseppe Tonetti, local contractors, from Kaapmuiden who had formally worked on constructing the Selati Line, were employed to repair the bridge. So off they went through the bush, back to the Selati Line, fetched the necessary supplies left lying at the side of the track, returning to Malelane with wagons full of necessary supplies. Twelve days later, a temporary detour bridge was in operation at Malelane, while repairs to the main line continued. In the meantime trains to Pretoria were again running on the 29 June 1900. Just less than fourteen days after the sabotage.

No! The Selati Line is not Lost or Gone Forever

Later, Steinaecker’s Cavalry Corps, who had their official headquarters at Komatipoort with their depot at Pietermaritzburg, – Natal. British High Command’s next move, was to station ’S & Co’ at the Sabi River Bridge Camp in October 1900, under the command of Capt. F Francis, while Crocodile Bridge on route was placed under the command of Lt ‘Gazza’ Gray. As extras for living in wild Africa, each member of the corps were ordered by the military to received a daily ration of pickles, a daily quota of fresh milk, whiskey ‘to keep off the fever’ and ten shillings of pay. Their meat was to be ‘as much local game as they could shoot.’ And the milk, in the wilds of Africa, you may ask? No problem, the military was not specific about that, so the corps, probably by order of its head, was instructed to round up the local native cattle, impound them for safe keeping against marauding tribes and Boer commando’s, ‘until the war was over’ and milk them daily, – you can work out the rest.

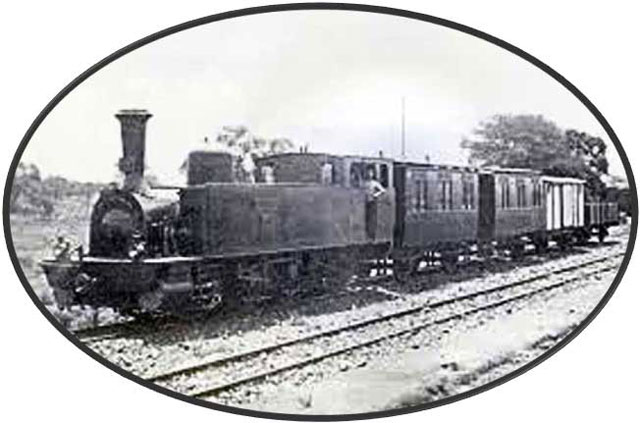

The corps now had a private train for transport on tow, with none other than the Selati Line service to and from Komatipoort. The train ran at least once a week; its usual driver was trooper Tom Boyd, a man overly fond of alcohol. But Boyd never needed to steer the train on the one line track, but he did need to brake at Komatipoort before he hit the Eastern line Y junction and on the other side, brake before he ended up in the drink on the other end at the Sabi River Bridge. This he managed, but died of alcoholic poisoning a short while before the corps was decommissioned. The exact locomotive commonly used by them is unknown, although it is described by Stevenson-Hamilton – first Kruger Park ranger – many times in his book “South African Eden.” It sounds by Hamilton’s description, more like one of the 20 tonners, the Durban or the Pietermaritzburg. The picture above is said to be Pump Willis standing at the cab of one of the 40 tonner Selati engines. Pump was the driver on this occasion having taken over as driver after Boyd died. With the war over in 1902, Steinaecker’s horse was decommissioned at Komatipoort on 7 Feb 1903.

After Steinaecker’s outfit had been decommissioned, one of the Selati loco’s with a “private coach” incognito, completed a trip to Sabi Bridge in 1903, with guests. This was described by the Warden as “the panting Selati engine,” having “a feather in its cap” for “completing the fifty mile journey” uphill (a mere gradient). Interestingly, the engine driver got £35 a month, plus allowances for extra time, even though he was almost never employed in his duties as driver.

Von Steinaecker, a little over five foot, had a Napoleonic complex, (short-man-syndrome) and made up for his stature by being a ‘perfectly disagreeable fellow’, ideally suited to the times and place he was in. Steinaecker and his men (who only wore plain clothes) were under strict orders from British High Command, not to let on to anyone that the unit was funded by the secret service. Instead they were ordered to make out their outfit was a privately funded militia. This seemed to be no problem to these gun toting hooligans at all, imbibing, carousing and generally acting like they owned the world. They also ended up killing almost the entire region’s remaining game population. After shooting most of the wildlife for fun and food, (using the animals as target practice from the train while in transit) they set up a sideline selling curios, biltong, skins and trophies to the British troops going back home, who passed through Komatipoort on their way to the waiting ships.

It was no secret where these men came upon their character. On the occasion of the corps’ arrival in Komatipoort, the commanding officer of the infantry battalion there, advised Steinaecker that ‘on no account were the town’s tame pod of hippos to be tampered with’. This order greatly aggravated Steinaecker’s sensitive nature and feeling he was being dictated to, ordered his men to ‘shoot the lot at once’. To the credit of his men, they decided to disregard the order.

Apart from being in the British Secret Service, Steinaecker was appointed senior officer of an area placed under martial law by the British Military and in so doing made this man the total law. The region proclaimed under martial law, covered a vast area from Swaziland to the Limpopo River and from the Mozambique border to the Drakensberg Mountains, an area way bigger than the Kruger National Park is today and he ruled it with about 300 hand-picked troops of his own choice. One of his tasks was placing troops at stations all along the Transvaal/Mozambique border. The officers’ mess and Steinaecker’s headquarters were situated at the old ‘Selati House’ at Komatipoort, which was built by the construction team that built the Selati Railway Line, until it was commandeered by Steinaecker and his outfit by order.

Steinaecker had a force of 40 men stationed at Komatipoort, who were euphemistically called “Steinaecker’s forty thieves” by the locals. This fact and others came to the attention of Forbes, the senior British Officer at Barberton, the commander of the entire Lowveld region, became extremely incensed. He put in a complaint to the War Commissioner, describing this outfits conduct as unbefitting a British military unit.

It may be of worth knowing, Steinaecker reported many men and horses being attacked and killed by lions during the war, mainly at the Sabi Bridge camp. This must have been an aftermath due to the many man eaters present during the Selati Line construction. Such was a case near Sabi Bridge, where a horse and his African minder were both killed. A short while after, one of Steinaecker’s regulars named Samuel Smart was also attacked and badly mauled at night at the Sabi Bridge camp. He was taken to Komatipoort by train for treatment although he later died on the 4th October 1900, from his wounds. At this same time, Steinaecker was pursuing a Boer force commanded by Coetzee up the Selati Line with 40 of his own men and 50 other conscripts, from two British cavalry units. Included in this raid, were two other outfits from the Australian and Tasmanian Mounted Rifles, but the Boer forces proved too strong for them and drove them back to Komatipoort.

A Sad Military Man in His Private World

After the war, Steinaecker applied for a transfer to the British military proper, but was refused and most likely because of the rumours of his conduct in Komatipoort. Tom Casement, the Mining Commissioner at Barberton, had reported Steinaecker and other troops to head-office for poaching. The capers of Steinaecker’s horse were also well known to James Stevenson-Hamilton, who remarked on the damage done to wildlife in the Sabi Reserve by this outfit during the war. Although Maj. Greenhill-Gardyne, adjutant of the corps at Sabi Bridge was the official “wildlife preservationist,” had little to no control. Concerned with the game depletion, he did play a key role in conservation and was much help to the warden with the records he had kept. These records are for ‘natures sake’ he purposefully conveyed to Stevenson-Hamilton (warden) after the war.

Following a failed farming venture at his farm, ‘London,’ at Bushbuckridge, Franz von Steinaecker ended his own life. The incident happened after a very heated and drunken argument with a good friend and fighting compatriot, John Edmond Delacoer-Travers. Travers owned the farm ‘Champagne’ in the same region, on the road to Acornhoek, where Steinaecker had been invited to stay. Although a guest, Steinaecker saw fit to regularly badger his host on matters concerning the military. Insulting the British out of revenge and wholly rooting for Germany to win the war. Travers had learned to turn a deaf ear, yet on this occasion, his guest became violent, insisting that the Germans would win (WWI). Travers had had enough and called the police. On their arrival, to avoid arrest, Steinaecker took a strychnine tablet, dying on the spot, on 30 April 1917, at the age of sixty-three. He was buried in an unmarked grave at the Bushbuckridge cemetery.

See you for our next Selati Line adventure: Stevenson-Hamilton – Sabi Reserve