Okavango From The Bottom Up and Top Down

A trip like no other?

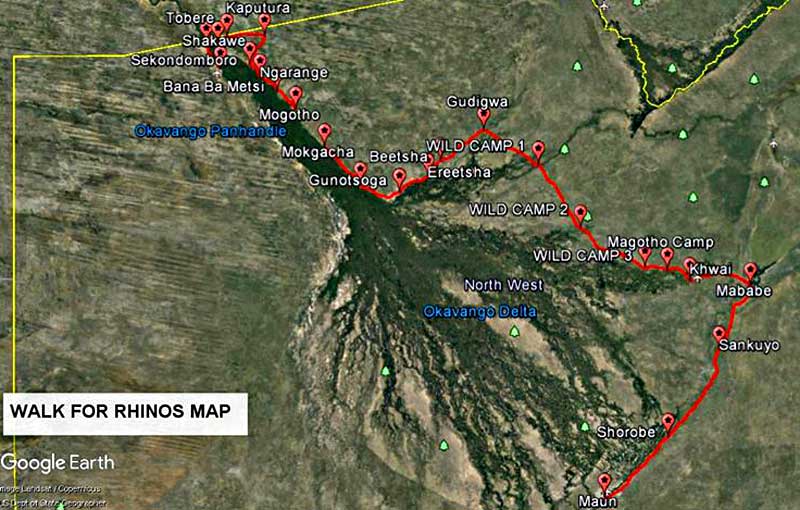

This article is dedicated to the Walk For Rhinos 2017 and especially for Kane Motswana – ‘Kane the Bushman’ on Facebook. This walk is from Shakawe to Maun, some 300 miles – 500 km – around the north-eastern side of the Okavango.

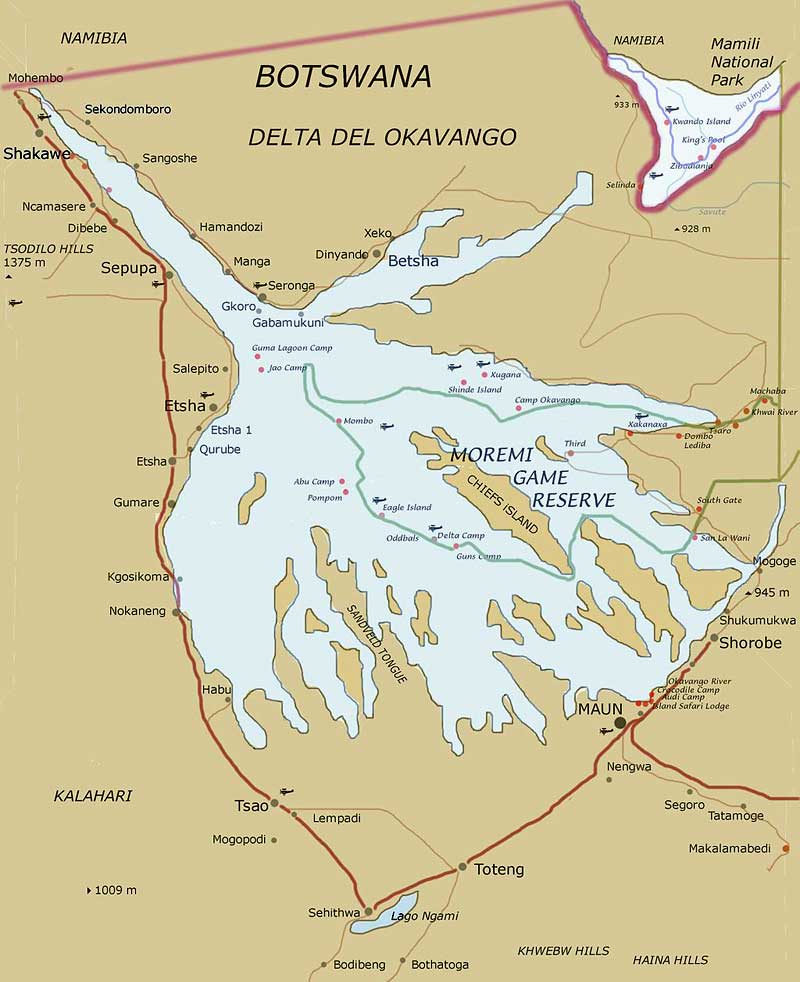

Do, or should I say, did I know the Okavango? The Okavango Basin stretches some 13,000 sq km (5,000 sq miles) and is one of the Seven Natural Wonders of Africa. I have traveled up, down and across the delta a few times. To say I know the region, would be a gross misrepresentation of facts. But I will share a part with you, of the little I do know.

It all must have started in the early seventies – because I don’t remember the sixties! It was a quiet, overcast, sultry day in late summer, on the banks of the Jukskei River, somewhere near Hartbeespoort Dam – which side, I can’t actually remember either.

While minding my own business, staring into the gently flowing water, I heard my name being called, some 400 meters into the bush, beyond the opposite bank. After answering, I waited for the mystery female voice to appear. It materialized into a young woman struggling through endless khaki weed, sporting a pink tracksuit now bedecked from her shoulders down to her ankles with tiny, black spikey seeds. She resembled the Pink Panther, with bad five-day old stubble everywhere. Recognizing my visitor as Kim, the wife of a friend and longtime African explorer, I waded through the shallow water to the other bank to help her across.

Kim’s news was short, yet unbeknown to me, it was about to change my life in a major way.

“National Geographic need you to guide them through the Kalahari to film Bushman, there and into the Okavango Delta, up to Angola.”

“You can’t go through the Khoisan Kalahari territory in Botswana. And besides, there is a war on in Angola!”

I replied, before explaining to her how futile her efforts were to remove the blackjacks from her tracksuit.

“Best leave them on until we get back to camp.”

“Thanks. We must hurry, gather your stuff, they’re waiting,” was Kim’s quiet reminder.

Back at camp, I got the whole brief on the Geographic team’s plans and purposes. It came about that they had already received permission to travers the San region of the Kahalari, from the President of Botswana, Sir Seretse Khama.

That was amazing. The only group to get the same privilege in some thirty years was a French anthropological research team, two years before.

The exclusivity of a trip with National Geographic was certainly significant. Especially since the expedition was to find, film and study the – Bushman – Khoisan people in a restricted region preserved for their natural habitat. The resultant documentary was to be made about their general and sociable habits, as well as their hunting skills and food gathering methods. And any artwork that might be found in the region was not excluded. Also of interest to the accompanying anthropologist was their music. So, we were all in for an unusual treat.

The ‘main man’ in this expedition was a famous American anthropologist – proficient in the Khoisan culture. This man – and associates – had spent extensive time studying the Khoisan some decades before and this trip would retrace his steps to the point at which we diverged, departing on to the Okavango delta.

Three space images of the delta joined into one. (source)

Our itinerary would take us from Johannesburg South Africa to Gaborone in Botswana, up through the middle of the Kalahari to Ganzie. From there on, we would travel to Maun, into the Okavango, on up to Shakawe – at the Caprivi Strip – by boat. Then by land to the Tsodilo Hills and from there, to Chobe Lodge via Croc Camp – Maun – and back to Johannesburg. The trip would take approximately five to six months. As it was, some footage was not up to National Graphics standards, resulting in a flight back to Ganzie for a re-shoot at Tanakas’ (Japanese anthropologist) borehole.

Spending a fair amount of time with the Kalahari Khoisan, who have a passion to teach – interested people – how they function and live, I thoroughly spoiled myself in just sitting and listening. They believe they have a message to the world to live a simple life, leave your troubles with God, be frugal and productive in yourself while helping needy people. This is quite in contrast with most other isolated tribal peoples of the world who are not monotheists as they are. And unlike any other primitive peoples of Africa. To think of other needy people is also out of the ordinary. It might do you well to know that these people believe to hurt another human being is to hurt yourself. It is embedded in their minds from childhood. I was obviously asked where, what and why I was there. I told them and briefly mentioned the party was headed to the Delta to film the River Bushman – also a Khoisan people much like themselves. Suffice to say, this stirred up a hornet’s nest of questions and answer time for me.

I had no knowledge of a people, like the Khoisan living in a desert water-land, because I had always learned Khoisan lived where water was scarce. These ‘River Bushman’ – one of the best kept secrets in the delta – have existed on the islands and edges of the Okavango delta swamp land, for as long as they have known their own history. I was very hopeful I might be able to have meetings with them myself!

The clan in the Kalahari begged me to convey their greetings. Khoisan, you may not know, are a very interactive people. This is immediately observable with their children, in the folktales they tell and in their dances depicting hunting and other life experiences, which are not to be missed. To understand the San man, you have to switch off and leave your troubled mind behind when you deal with them. I found no one among the western team who could empty themselves enough to be let into their hearts with confidence. Because I was their interpreter, I found them sadly using me more than I would have liked, as their mouthpiece.

In case you are wondering about the names used, here is a brief outlay. The term Bushman or especially ‘Boesman’ is frowned upon today. They are now known as the Khoi and San – or Khoisan – with only two tribes /Gwi and !Kung. Real tongue twisters for western cultures to pronounce correctly. And these make up the sum total of the once well-known Bushman ‘Boesman’ people. The San had no name as a peoples or tribe and referred to themselves simply as the people of the land. Recently our western culture was to recognise them as the Khoi and San and this is still not entirely settled as of yet.

Our convoy consisted of three, safari-ready Land Rovers prepared for expeditionary travel in Cape Town with overhead hatches from which to film and take stills. Included in the bag was a converted ex-military, 7 ton Bedford 4×4, beefed up a little. We traveled through the Kalahari, spending time wherever we found occupied San camps. And, when our water supply carried in the Bedford , which I drove – in 44 gallon (US 55 gal)(200 ltre) drums – started running low, we moved on to a San settlement called Tanaka’s borehole, established by the Japanese anthropologist of that name.

There was a hand pump at the borehole – also a small diesel engine that worked when diesel and an operator could be found. Here two small tribes of the Khoisan had settled. This is where we camped for some time, while script, filming, and editing was done. Every move of the Khoisan was scrupulously observed, filmed, photographed and written about for months – even their hunting skills included. When satisfied that all had been meticulously recorded, in everyway possible to us, we moved on to the Okavango Delta. FYI, the Okavango is, in fact, a flooded desert region where the waters eventually disappear into the sand. Where to, no one yet knows.

Makoro punting boats. Carved from hollowed out trees. (source)

Arriving at Maun where the Okavango ceases to flow, the team split up into two parties. One went up through the swamps in two boats equipped with water-proof, 16mm, French-made, Beaulieu Cameras in hand, with the aim to find and film the ‘River Bushman’ and the underwater aquatic life surrounding them.

I took the other half of the team, – at my own cost – because the American team forgot to leave us the money at the Croc Camp desk in Maun as arraigned. These consisted of all the vehicles, drivers and support staff via Lake Ngami, on up the western boundary of the delta to Shakawe bordering the Caprivi Strip and the Angolan war. After filling the 200 litre drums of water and fuel, – carried in the Bedford truck – then stocking up with enough food for the whole trip we left. Arriving at Shakawe first, we waited for the river team.

When the anthropologist, producers, directors, camera crews and sound men arrived at Shakawe, the expedition moved on with the vehicles to the Tsodilo Hills for more filming. My choice was to find the River Khoisan myself and I left the National Geographic crew, choosing rather to go back with the two boatmen and the boats. The plan was to meet up again in Maun.

From Shakawe to Maun airport is a distance of 150 miles – 240 km – and by water, it ends up at some 350 miles – 560 km. That trip is one I will never forget! If you have never seen the delta, my suggestion is to put it on your bucket list, immediately and it will be the best bucket list you have going.

I found some of the swamp’s Khoisan people on Chiefs Island the island in the middle of the swamps, at a camp where they were spending the night, obviously living in perfect harmony with their abundant water. Very much unlike their desert cousins, for whom water is a rare commodity.

After leaving those fascinating people, I stopped for a week at my friend’s camp on Chiefs Island before going on to Croc Camp at Maun. The one fiberglass boat was our own – my father and I – and the other, an aluminum one, was mainly used for cargo and belonged to my friend, a co-owner of Croc Camp where both boats lived.

I met up with the team back in Maun for the next trip up the East side of the swamps to the Chobe River, where another large amount of data was collected and recorded. Spending a little over a week at the Chobe Game Lodge, we went back to Maun and then on to Johannesburg. (some of the most famous people in the world have stayed at the Chobe Game Lodge.) How about Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, Prince Charles, former U.S. President Bill Clinton, Kings, Queens and many more, check it out.

Go find yourself an expert survivalist! A San man, who will teach you the things of the bush and I know you’ll be in the best hands and you’ll never forget or regret the experience.

Get led through the natural bush by its natural people, the Khoisan. They will point out the traditional ways in which they found their daily bush food and if you ask, they will share their many secrets of the wild with you. They will teach you how to track and what to look out for when you next go wandering in the wilds alone. Our senses are naturally highly tuned, but become dulled in our electronic, modern world. We need to know how to reignite them in the quiet of the bush, to better experience it’s secrets – and ours.

I hope you have as much fun as I did those many years ago. I have done everything from boating, flying, fishing and pulling hair out of sleeping elephant’s tails and I still have not had enough of the swamps.

The Khoisan people have now formed a trust with the government in and around the Okavango region, where they live and take tourists as a means to survive, seeing they are no longer allowed to hunt. The guides will escort you through their land – in good English too and some speak Afrikaans as well.

As much as it is impossible to know the swamps, it is equally impossible to describe and the best offer is a video. And even this does it little justice.

Video run time: 1:00:53 minutes. Sometimes it takes a few minutes to come into focus. If it doesn’t, go to YouTube.