Selati Line – Part VI

Selati Line – Part 6

Selati Line and the Kruger National Park

James Stevenson-Hamilton to the Rescue

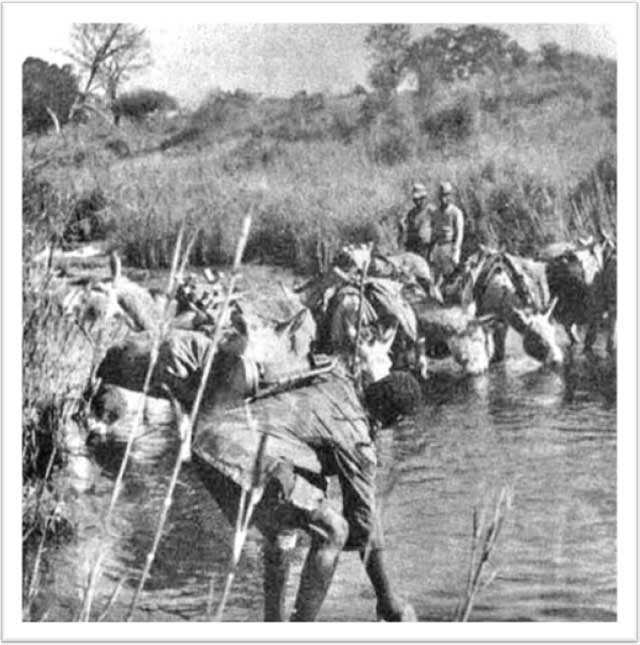

This Scotsman, who came to live at the end of the Selati Line as it was then, – having been abandoned in 1894 – loved this country he came to know. Then, overcoming the hardships of the bush he settled in, in spite of the opposition he encountered. He had much to overcome, without the human side of petty in-fighting, jealousy, language barriers, exclusion from board meetings and low pay, yet he forded on for the cause he believed in. The man was no quitter. This warden’s days at the Kruger National Park, would have been short lived, had he buckled under the strain of hatred and opposition he came against in his 44 year tenure. I, for one, am pleased he stayed the pace. Two actions personify this man’s character, which is well illustrated in the following paragraph.

In his early days; around 1907, he gave up a large part of his own salary to get the much-needed ranger Healey and staff appointed for the 4,000 square miles of the park above the Sabi River – the Shingwedzi Game Reserve (1908). Next, a remarkable display of sacrifice for the cause of the Kruger Park and best said in the warden’s own words. “I held a probably unique position in having concluded twenty-five years of government service on a lesser salary than that which I had started…” “Healey was therefore duly gazetted early in 1908” Healey however volunteered his life for freedom and died in 1916 fighting for his country (WWI 1914-18). What a wonderful testimony for Healey’s friends and family, to say he was a ranger in the Kruger National Park, before offering his life in the call of duty and all because of the warden’s personal sacrifice.

To begin with, Stevenson-Hamilton after his appointment as Chief Warden, stayed at the Crocodile Bridge camp in an old disused mielie (maze corn) storeroom, made of corrugated iron and only later moved to Sabi Bridge. As a result of the Steinaecker’s horse outfit. He had to wait for them to be decommissioned and for their martial law to be rescinded from the region. Sabi Bridge during this period was occupied by the military and the members of Steinaecker’s Horse, preventing the warden from taking his proper residence.

Not until the end of the year, (1902) did Stevenson-Hamilton meet von Steinaecker for the first time, the latter had been in England for some five months, trying to get into the British Army. But thankfully Steinaecker was decommissioned a short while after this meeting and the warden could now move to what was his new home and head office at the end of the Selati Line at Sabi Bridge. For some inexplicable reason, Steinaecker without any instructions, ordered all the buildings at Sabi Bridge to be demolished, hence the storeroom, large stables, and several other outbuildings were razed to the ground. All the stock and construction materials were loaded on the train, but due to a shortage of time, the blockhouse was spared, although orders had been given by Steinaecker, to destroy it as well.

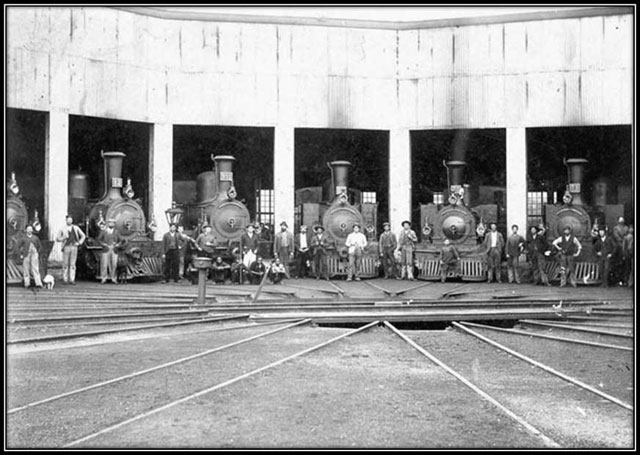

Not long and the Selati Line became dubbed the rangers ‘private railway’ and it remained so for 10 years until the South African Railway’s completion of the line to Tzaneen. First order of business was the completion of the Sabi bridge (see picture at Selati Line – Part 1), crossing the Selati River in 1912; (now called the Nxalati River) then another short delay before extending it on to Soekmekaar, thus joining the main Pretoria northern line to Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). This facilitated trains from land-locked Rhodesia to Delagoa Bay port for trade. At this point, the Selati Line train service commenced in earnest and remained a single track until it was abolished in 1973. ‘Abolished?’ Yes, it was obliterated, but not before it made an indelible stamp on the Lowveld forever.

Sabi Bridge kept its name and remained so for 34 years until 1936, when it was renamed Skukuza by the Parks Board, after Stevenson-Hamilton’s local name. Tradition holds that it was a Chief of the Ngomane tribe who named Stevenson-Hamilton, ‘Skukuza’, which is interpreted – ‘he who makes things upside-down and inside-out’ – as a result of his no-nonsense clean-up policy towards the entire regions poaching.

Selati Line gets a New Twist in the Tale

The Selati Line’s twist in the tale firstly began as a service to the Sabi Game Reserve and later extending its services to other major parts of the Lowveld, Bushveld area.

‘How did this happen?’ You mean the extension of the Selati Line? ‘Yes.’ Well, there was an overflow of money from the Transvaal Republic, of some £2, 000, 000 that needed spending somewhere, so the Selati Line became the somewhere for it to be spent. The Transvaal was the only province not in debt at the time of the S.A. Union – somewhat of an irony due to the 1877 British annexure. South Africa was being unified into four colonies to form the new Union of South Africa, (after the Anglo-Boer war) and the government of the Transvaal Republic was to be incorporated into this new South Africa in 1910, as one of its colonies. ‘And the game reserve.’ Game reserve you say? What game reserve?

It was like this, you see. Two bad things, caused a good thing and then this good thing, caused a bad thing etc. In the end, it was all turned into a good thing. Now let’s explain. In 1896, the Rinderpest, – bad thing – was wiped out as a result of the merciless killing off of the game herds, – bad thing – which in turn exterminated the dreaded tsetse fly – good thing, – which was the cause of sleeping sickness (nagana) killing man and animals – bad thing – that kept development away from the Kruger National Park – good thing. When the tsetse fly had not returned as expected, the game populations started multiplying once more – good thing.

One day on closer inspection by the Government, it became obvious that the game reserve region was well suited to agriculture and the idea of new settlements, was the order of the day – bad thing. So bye-bye game reserve, because as long as there was the tsetse-fly, they could keep the reserve, but now that the tsetse-fly was gone, the game reserve must be gone as well. Right? Well no! Now the people have a game reserve – good thing. Right? – (Of interest, is that Rinderpest (sleeping sickness) was finally eradicated worldwide by 2010).

So, to prevent the surplus money from the Transvaal Republic’s Treasury going to the Union in 1910, de-proclamation of the Game Reserve was touted by the minister of transport. He, putting forward that the railways with a new agricultural region would bring in bigger profits and many in the government agreed. While this was going on, the drive was under way to make this entire region of the Transvaal Lowveld profitable in terms of the railways through agriculture. And so, the money was allocated for extension and expansion of the Selati Line Railway, for development of the entire region, in the name of progress.

In the meantime, the Selati Line had changed hands, to be owned by the Union Railways (the government), who contracted out to Pauling & Co. Consequently, work on the Sabi Bridge commenced immediately in 1909, where the line was extended to Tzaneen in 1912, (close to its original destination) and on 25 October 1912, the Sabi Bridge was officially opened. Pauling & Co brought in and used their own labour force and no locals or outsiders were employed (this was the government).

It’s All in the Development

Out of necessity, there developed a small siding at Sabi Bridge, although to Stevenson-Hamilton’s amazement and that of many others. This siding was for loading on and off of passengers and goods. Also needed for the steam locomotive, was the taking on of water. This was set up north across the other side of the Sabi River and the bridge, called Huhla, (still on the Selati Line) but built there by the Union Railways. And this is where all the post, rations and deliveries for the Sabi Bridge camp were subsequently offloaded in the middle of the veld and what’s more, at all hours of the night only, – where there was nothing more than a water tank (and the monkeys & baboons?).

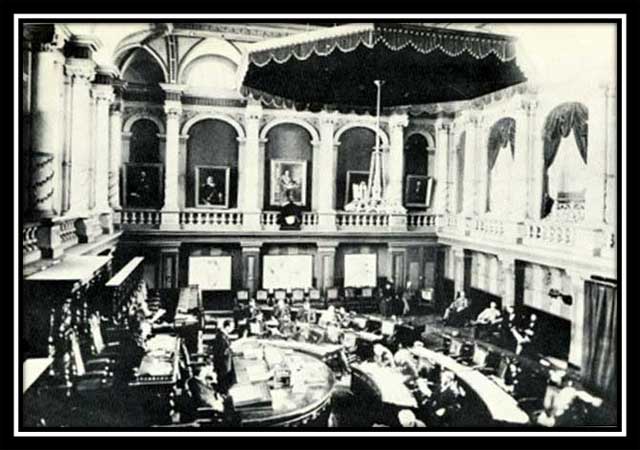

Many people perceived the Union Railway and later the S.A.R, (South African Railways) had no intention of acknowledging this reserve anyway, hoping it would go away, amount to nothing. So, this kind of contempt became the order of the day. And a cold war developed. This was borne out many times over the years and here is an anecdote 10 years on, as described in the following statement from the warden’s own notes (abbreviated by me), which regarded the 1923, meeting at the Old Government Building, Pretoria, to indicate how much bad sentiment was going around about the reserve.

“I felt rather as I suppose a shepherd might when a pack of wolves threatens his ewe lambs”… “One after the other the delegates got up and stated their requirements…” “railway interests, coal, gold, sheep grazing, cattle ranching, cotton and orange farming; each claimed its bit.” Then “as one suggesting the merciful coup de grace for a suffering animal, Sommerville, the Secretary of Lands, rose to his feet, and said: “My department wants the whole Sabi Game Reserve abolished.” “Well,” remarked van Velden, the Provincial Secretary… “who then informed the delegates that we would think over their requirements, and let them know later what we had decided to do.”

As you can imagine, this was a very scary time for the warden and all involved with the Park at large. One can only imagine how they must have felt at such a time like this, with the great depression in the middle of two great world wars. And, if not for van Velden we would have lost the Kruger National Park forever and with it the single most valuable GDP earner in the country, way surpassing the GDP for all minerals combined. Notwithstanding the Parks ambassadorial status to the world incorporated.

See you for our next Selati Line adventure: ‘When the Sun Went Down’