Selati Line – Part 1

Kruger Park – Gold Fields

A Story to Remember

If you’re someone with insider information, you will know how the Kruger National Park, South Africa’s largest national park, nearly did not exist, as a result of the Selati railway line. See how the Selati Line goldfields project first backfired on itself, died out, was reborn, then proceeded to change the face of tourism in the Kruger Lowveld forever.

A true African tale of wild drama. A story more suited to an Economic Europe, not for the unknown wilds of Africa. But happen it did and in the end, the good guys won. That is, if you know who the good guys were or not were? This story of intrigue and subterfuge played itself out when two French bankers (Baron’s, mind you) decided to build a railway to nowhere in the Bushveld, which became known as the ‘Selati Line’. The outcome and methods applied would amaze any big modern venture for gall, size and danger, not to mention, downright audacity.

The bribery, death, deception and skullduggery that accompanied these two bankers is almost unparalleled in the world, never mind Southern Africa, even to this day. It involved an entire government and the alteration of a large strategic region of the Southern continent, for ever. This railway is no more… it never reached its destination and never accomplished its intended purpose. Yet it had such vast and far-reaching impacts on the Lowveld, the Second Anglo-Boer War, the Kruger National Park and even across the world. That which was swept under the rug, has never been uncovered, but in this account, we get a glimpse of the truth.

I have wanted to write this Bushveld saga for many years, as a result of the amazing influences the Selati Line had on the whole Lowveld region. You be the judge after you have read the story. I invite anyone to drop me a line if you have more to add or take away.

Con or Swindle. You get to Pick.

In 1892, the Selati Railway Company was a shareholding company floated in Brussels (Europe) by two noteworthy bankers from Paris, Baron Eugene Oppenheim and his – older – brother Baron Robert Oppenheim. The number of shares and how much they were sold for, is not reported anywhere. A company was duly formed by their Franco-Belgian syndicate called ‘La Compagnie Franco-Beige du Chemin-de-fer du Nord de la Republique Sud-Africaine.’ This is translated as ‘The Franco-Belgium Railway Company of the Northern Territories of the South African Republic.’ Under which it established the ‘Selati Railway Company’ as early as 1892.

In 1893, the building of the line to the Selati River Gold Fields commenced. The intention for this new rail line was for transporting gold to and from the new Selati Gold Fields, to the rest of the world. It went via Komatipoort through Mozambique (then owned by the Portuguese) on to Delagoa Bay, the port then was called Lorenzo Marques and today is known as Maputo.

The line was to be built from Komatipoort over the Crocodile River, on to the Sabi River, over the Sand River, on to the Oliphant’s River and finally the Selati Gold Fields at the Murchison Range. Ending up near the town of Leydsdorp, way into the north country. Leydsdorp was named after W.J. Leyds in 1890. Leyds, a young Hollander, was then the State Secretary of the Transvaal Republic and a good friend of Paul Kruger. Leydsdorp is next to the Selati River, near to where Gravelot is today. At this time the Selati Line started it’s life at the newly completed line from Lorenzo Marques to Komatipoort. The newly built railway line from Komatipoort to the coast at Delagoa Bay, (a distance of about 60 miles) had been completed and inaugurated by the Portuguese on the 1st July 1891. The convenience draw card, not to be missed by the two French banker brothers was gold. As a result, the Selati Line was born.

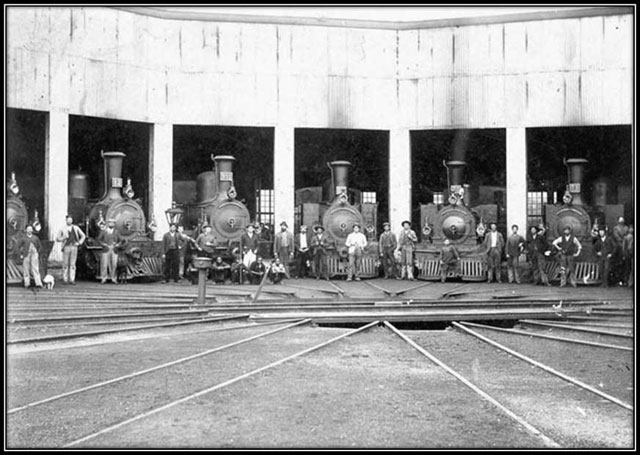

The way things dovetailed together has amazed me for years. This Mozambique Line was the rail line used by the Oppenheim brothers to transport even the smallest piece of equipment needed for their new (bent) venture. Komatipoort consisted of no more than a border outpost with more tents than tin shacks. To this outpost, the Oppenheim’s transported locomotives, freight cars, steel, sleepers, picks, shovels, carpentry tools, bridge building steel and believe it or not, European timber (from 6,000 miles away by sea) as well. The trains were also later used for the necessary food, booze and bar entertainment brought in by ship to Lorenzo Marques, from other regions, of the world. I’m sure you get the picture.

The lines (railroad) construction had been contracted out to the British company of Westwood & Winby, who built the first part of the Selati Line from Komatipoort to the Sabi Bridge (Skukuza) in 1893-4, a distance of 80 km. The rest of the line from Sabi Bridge to Tzaneen was completed by Pauling & Co., between 1909-12. The Oppenheim’s had bought no less than four high-quality locomotives. Two 20 ton 0-6-2T, Whythes & Jackson Limited locomotives, from Durban and Pietermaritzburg, obtained from the Natal Railway Company. Along with two 40 tonners 0-6-2T, built by Maschinenfabrik Esslingen, obtained from the NZASM (you will read about them further on). The Selati Line was to connect to the new Transvaal Gold Fields railway line at the junction in Komatipoort, which would run from Pretoria to Delagoa Bay. This was the line was set out for the transportation of goods and gold to and from the new Witwatersrand Gold Fields, discovered in 1886. This was later known as the Eastern Railway Line, from Johannesburg.

Joining the Dots in the Sand

This Eastern Railway Line was initially intended to run from Pretoria to Delagoa Bay. Its construction had been toyed with since 1866, by the Transvaal Government, primarily involving a Scotsman named Mac Corkingdale (who died in May 1871). Afterward came the British annexure of the Transvaal on 12 April 1877, through Theophilus Shepstone, leading to the 1st Anglo-Boer War. The Boers won that war in 1881. After the war Paul Kruger reopened railway discussions, with a Portuguese engineer named Major Joachim Jose Machado of Mozambique, to map out a line from Delagoa Bay to the land-locked city of Pretoria (Transvaal). The upshot, Machado was duly appointed chief engineer of the entire Eastern Railway Line. Later, the town of Machadodorp was named in honour of him.

At this time, alternate routes to the Cape and Natal ports were out of the question. These ports were closed to the Transvaal Republic, being controlled by the British and their forces opposed to the Republic.

The Eastern Railway Line had been ratified by the ‘Volksraad’ (council) of the Transvaal Republic in 1883. It was agreed the Portuguese build their own line in Mozambique, from Delagoa Bay (Lorenzo Marques) to Komatipoort and in turn, the Transvaal build their own line from Pretoria to join at Komatipoort. An American, Edward McMurdo, was given the concession for the Mozambican line in December 1883. For this work, the Portuguese established the ‘East African Railway Company.’ Yet they only set to work in building the much needed line four years later in March 1887. ‘This was a fine how-do-you-do.’ Why four years, you may ask? Well, read on. This is Africa, (TIA) remember?

Even more ridiculous was this new line under McMurdo, with (build distance 100 km) had not even arrived at the Transvaal border in 1890, seven years from its inception. Compare this to the 80 km Selati Line, built six years later from Komatipoort to Sabi Bridge, in a staggering one-year build, through the same bush country.

Of course, there would be extenuating circumstances to consider. No one wanted to work on this project, because of the dangers of fever (malaria and more) and predators (lion and hyena). This was eventually solved by employing a famed group of deserters from the British Army, called the ‘Irish Brigade’, haling from the Pilgrims Rest area, headed by George Hutchison (Captain Moonlight). One night, true to character, these deserters, in a drunken caper, wrecked the town of Eureka City (in the Barberton district) razing it to the ground, simply for fun. These mercenaries would work anywhere, except for the British Army. Hiring them was a smart move, considering a total of 250 Europeans and over 3000 Africans were magically engaged to build the McMurdo line to Komatipoort from Lorenzo Marques.

Finally, their problems solved, they went to work, completing the line (they thought) in 1888, until it was discovered the line was 5 ½ miles short of Komatipoort. After a brisk and fast court case (in Africa); lasting a mere three years, between the Mozambique Government and McMurdo’s company, the East African Railway Co., the case was resolved in favour of the Government. Work resumed and the line was completed in May 1891. As I have previously said, ‘taking six years’ to complete.

Whereas the 370 km line from Komatipoort to Pretoria, under construction from both ends by the Transvaal Company, the Nederlandsche-Zuid-Afrikaansche Spoorwegmaatschappi – NZASM – (Netherlands South African Railway Company) was completed on 20 October, 1894. This finalised the long-awaited connection to the sea between Pretoria and the new port at Delagoa Bay (Lorenzo Marques). The line was officially opened on the 8 July, 1895, by Paul Kruger, the President of the Transvaal Republic. This was the Republic’s only official access to the sea (bypassing all British occupied regions). This also brought an end to the short, but famed, Delagoa Bay & Goldfields transport wagon trail.

See you for the next adventure of the: Selati Line – To the Sabi Bridge