Selati Line – Part 2

On To the Sabi Bridge

They All Cried, “Corruption!”

To recap:… In 1893, the Selati Railway was to be the new line to the Selati Gold Fields, situated around the Selati River near Gravelot, where a mine is still operating today, albeit, not much gold. In 1865, a teacher – geologist and explorer – Karl Mauch from Germany, suggested there was gold in ‘them-thar-hills’ near the Selati River. See the map below at the 8,725 foot Mauch Peak, named after this man. It might be of interest that Karl Mauch recorded the Great Zimbabwe ruins on 3rd September, 1871. Later in 1871, a party consisting of Edward Button, James Sutherland, George Parsons and Thomas MacLachlan, followed Mauch’s trail and the found the gold he had reported on. The mountains where the gold was discovered, they named the Murchison Range (named apparently after the great geologist, Sir Roderick Murchison) and reported it to the Transvaal Government, as the law required. A government official was sent out and confirmed it was a workable gold region. What ensued was a gold rush to a very inhospitable area, considering the gold was sparse and only a small town was established.

And of course, the Oppenheim banker brothers from France, somehow got wind of this find. Then believing this claim to be rich, applied to Paul Kruger’s Volksraad, for the right to build a private railway line from Komatipoort to the new Selati Gold Fields. Now, things really get complicated. How the xenophobic Volksraad was persuaded to grant this right to a foreign private investor was no secret back in the day.

All the newspapers in South Africa, as well as England, Australia, New Zealand and the rest of the interested world, carried the stories of the Oppenheim, Volksraad corruption. It was bribery all the way from the lesser members of the Raad to Paul Kruger himself, President at the time.

No History Makes for an Uncertain Future

A small digression is necessary. Swaziland, an independent country, is to the south of our Selati rail region. For generations the Swazi’s had claimed this Selati Railway Line area, as their land and to this end, fought any tribal intrusion every year, thereby creating a buffer zone to keep themselves safe and independent. Every year, these wars took place from the Swaziland northern border, sometimes reaching out as far as the Limpopo River, (see the maps) farther to the north and if needed, even beyond, into what became Rhodesia – and today Zimbabwe. These war exercises usually took place every winter, when the trees were bare and the grass was short. Large scale hunting also formed part of this exercise, because disease was absent and the meat was good for the hunters and the army, turning the escapade into a long (biltong) supply-chain holiday.

From the early to middle part of the 1800’s, Swaziland faced some major threats to its safety, not only from the north but also from the south of the country. To protect Swaziland’s southern border from any Zulu ‘Mfecane’ (ethnic cleansing, from Chaka) and the ensuing war years, which also brought many warring tribes on the northern their boundary. At this time, the Swazi’s had become weary of wars. Then Swazi king Mswati II, made a plan for his northern boundaries protection, ceding the rights over the land between the Crocodile and the Limpopo River to the ‘Lydenburg Boer Republic’ in the 1850’s. To the Swazi king, this was a trade-off, or peace treaty, for the protection he greatly needed, from a people he believed to be a non-warring tribe of whites. Strangely enough, his move ended up paying off handsomely in securing the Swazi people and their borders in the north. As a result of this pact, the Swazi’s could concentrate on the threat from the Zulus in the south (its king at the time being Mpande), half brother to Dingaan and the assassin of his half-brother Chaka. Mpande had an expansionist policy. Securing his northern border was a clever move to avoid fighting a war on two opposite fronts. Other than the Zulu’s, the Swazi king was already dealing with other threats from the Tsonga/Shangaan people from the Gaza region in the south-east.

A little while later during the early 1880’s, after the death of Zulu King Mpande in 1871, it became necessary to establish a permanent northern border between Swaziland and the Transvaal Republic, where the new Eastern rail line to Delagoa Bay was intended to go. The Transvaal Republic wanted no disputes of land ownership with Swaziland during or after the build. At this time, the region between the northern Swaziland border up to the Crocodile River had been claimed by the Swazi’s after the native wars.

Before the rail line could be mapped and built, the border had to be defined. The persons chosen by the Republic for the negotiations with the Swazi King Mbandzini, were Able Erasmus (a man with stakes in the Transvaal Republic) and George Hutcheson a trader. Both were well-known to the Swazi King. Able Erasmus (native name Madubula, ‘he who shoots’) was a very capable explorer, hunter, cattle breeder, and negotiator who spoke the Swati language fluently due to grazing leases with the King of Swaziland for years. Later, after the Boers defeat in the Anglo-Boer War, Erasmus was appointed native commissioner at Lydenburg, under the British Union of South Africa. In the negotiations and remunerations that took place at the Lomati River, the King relinquished Swaziland’s claim to certain territories in favour of the Republic. And so the NZASM line was built and the Swaziland/Transvaal border was established as it is to this day.

Most of the immediate region we are dealing with here in this story, became controlled and owned by the government. Except for other isolated tribes in and around the Kruger Park who were paid rent for services – i.e. grazing – by the Kruger Park. This continued until the land was bought by the British Union of South Africa’s Government. The tribes of the south in the Crocodile River region were generally divided as follows.

The first modern native people of this area were the San people, otherwise known as the Bushman, evidenced by their cave paintings in the region. The next occupants who drove out and took over from the San were the colonizing Sotho and Tsonga speaking tribes from upper Africa. These included the BakaNgomane, some of whom were driven off or absorbed by the Swazi’s, who’s war policy was to subdue and absorb. An interesting point is Swaziland’s native name is KaNgwane and the Swazi people are known as the BakaNgwane, which refers to the people of Ngwane.

In 1896, Shangaan refugees from Mozambique integrated with the Ngomane tribe of the Crocodile River region. Part of this area and Gazaland (Mozambique) was also occupied by the Tsonga Chief, Soshangaan and became the Shangaan people, as they were later named. Then under later after his father died Soshangaan’s son, Chief Mzila, moved the Shangaans to the Acornhoek area known as Gazankulu.

Upside Down, Inside-Out Economy

For more clarity and a better understanding of this time period, some further history is needed for a very fast tracking economy, loaded with gold.

- The first Anglo-Boer War had just been fought ten years before, between 16 December, 1880 and 23 March, 1881. By 1899, most money and personnel associated with the Witwatersrand Gold Fields were in Britain. There were, of course, large contingents of Irish, Canadian, Australian and American investors. America had just experienced the worst winter in living memory, killing cattle and livestock, wiping out many a farmer and it was these who now ventured out seeking their fortunes in gold.

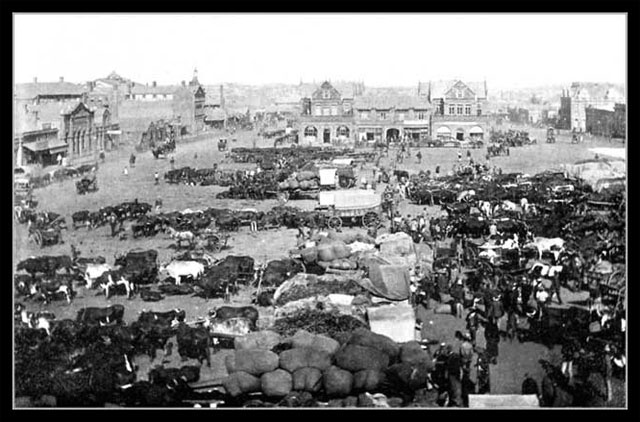

- At this time, Consolidated Gold Fields of South Africa marked an annual profit of 2.1 Million Pounds, becoming the largest return ever recorded by a limited company listed at the London Stock Exchange. This yielded a 125% dividend in 1895. The white population of Johannesburg at this time was 50,000. Apart from the few mentioned above, most came from the Cape and Britain, with only 6,000 being Transvaal burghers.

- The Sabi Game Reserve between the Crocodile and Sabi Rivers (the lower southern Kruger Park) was about to be proclaimed by President Paul Kruger’s Government, which was duly done in 1898. The reserve covered an area of 4,002 sq miles (10,364 square kilometers). Then in May 1903, the Shingwedzi Game Reserve to the north was added, forming the upper northern part of the Kruger National Park and with additions and subtractions was an area of some 19,485 sq km (7,523 sq miles).

Subterfuge Was Not a Submarine

As you can see, there were a substantial number of local residents available for labour to build a railway line, yet few were used. In an account given by Warden Stevenson Hamilton (first chief warden of the Sabi Game Reserve) in a book by him, he referred to numerous experienced railway construction workers, both white and black who died during construction of the railway. So where did they come from? My version you will read further on in this story.

The cost of the Selati Line amounted to £9,600 a mile, instead of the standard £7,200 a mile, which was the accepted norm for that time. This, among other things, made the Selati Line the most expensive railway line in the world at the time. More about that later.

The Selati Railway Company contractors under the Oppenheim brothers went ahead and laid the 80 km {50 miles) track from Komatipoort to a camp known as ‘Sabi Bridge’, (named by the famed Steinaecker’s Horse outfit) on the banks of the Sabi River, at a point where the Skukuza camp now stands in the Kruger National Park. The next step was to build a bridge across the Sabi River. This bridge was to conform to the newly completed bridge across the Crocodile River, built only months before by Westwood & Winby in early 1893 (damaged in the 2000 floods of this region).

See you for the next adventure: Selati Line – War Spies, Corruption and Death

Site Map