Selati Line – Part V

Selati Line – Part 5

New Take on Things at Sabi Reserve

I Think the Skullduggery is Slowing Down

With no train or driver at his disposal. The use of the train from Sabi Bridge was taken away from Stevenson-Hamilton, even though as the new warden of the Sabi Game Reserve he was stationed at Sabi Bridge. The warden was forced to first use a push-along and then a hand pump rail trolley for transport, as you can see from the photos. The lower picture was taken around 1907, sporting his team along with Ranger Thomas Duke. These trolleys were generally used as transport for maintenance teams on the railway lines and sometimes to repair and maintain telegraph wires along the tracks. The warden had the chairs fitted.

According to Stevenson-Hamilton, his weekly trips shopping for supplies at Komatipoort took him around five hours down the line and as he put it “twice as long to return”. Using the first trolley, the time was days and depended on the energy, weight of cargo and willingness of his team for the up journey back to Sabi Bridge. There are two photos of trolleys that Stevenson-Hamilton used; the third photo is the one on display at the Skukuza Station today and not one he used, but a more recent addition. It is said that this third trolley was used for transporting tourists short distances down the line or across the bridge for sun-downers, quick tours. The beginning of this tradition you will read about further on in our adventure.

Stevenson-Hamilton’s on the Left with His First Trolley at the End of the Selati Line. He Called this One the “Goods Trolley”

How They Were Stacked Up

There were two wardens and some game rangers appointed and commissioned before 1902, but for this story we will stay with the stayers as we knew them then. The Vereeniging peace treaty was signed in May 1902, marking the end of the Anglo-Boer War, when Henry (Harry) Christopher Wolhuter (a tall strongly built trim figure of a man), was decommissioned from the Steinaecker’s horse war outfit. Harry was born in the Cape Colony and migrated as a child with his parents to Legogote, bordering the reserve on the west side. Now at the age of 27, he joined Stevenson-Hamilton as the first official game ranger of the Sabi Game Reserve in August 1902 and was stationed at Pretoriuskop. Serving in two wars Harry ended up in two fronts of the Selati Railway Line. First as a sergeant to the Steinaecker Horse outfit and then as the first ranger to the Kruger National Park. Harry Wolhuter had been a farmer and storekeeper in the Lowveld at Legogote before the war. Harry was also the only one of nine troopers to survive black-water fever on a British hospital ship docked in Delagoa Bay.

This resilience, would stand him in good stead on the evening of August 1903, when he was attacked by one of two lions while riding his horse on ranger duty near Satara. One lion jumped onto his horse’s flanks and the reactive force threw him out of the saddle to fall right on top of the other lion, who thankful for a free meal, summarily sank its fangs into his right shoulder. Harry’s lion proceeded to drag him a distance of 94 yards on his back – later measured – over rocky ground and because it straddled him its claws ripped wounds into his arms while it pulled. To worsen his wounds, his regulation spurs were digging into the ground, causing them to be pulled off by the lion jerking its head to pull harder. The first lion chased after Harry’s horse, which in the skirmish got away, with his dog “Bull” (a Boer-bull breed) hot on the lions heels most likely thinking Harry was still on the horse.

Through the immense pain, Harry’s mind was racing, ‘where is this lion taking me’ and while he wondered, a sense of despair came over him, thinking this was not a nice way to die – and still so young. The most agonizing thought over and above his physical pain, was that which is described here, in his own words; “in addition to the pain was the mental agony as to what the lion would presently do with me; whether he would kill me first or proceed to dine off me while I was still alive!” He knew this was done to other animals preyed on by lions. All of a sudden, he remembered his knife at his right side and the same side the lion had him by the shoulder. Hoping it was still in its sheath and adding to his extreme pain, he gingerly reached round with his left arm under his back while he arched it to avoid his arm being striped by stones, at the same time desperately trying not to alert the lion that he was still alive. Hope of all hopes, he caught hold of the knife handle and like a drowning man clinging to a piece of driftwood, he hung on. After drawing his hand back, he slowly positioned himself, aiming at where he supposed in the darkness to be the position of the heart. As Harry took aim to plunge the knife blade into its heart, the lion stopped pulling and dropped him to the ground. Despair welled through his entire being. Was this it, is this the moment? The lion however, remained still, just standing over him. Seeing his chance and with frantic speed and torturous effort, he struck twice into its right side using his left hand. Then with equal speed, he sank the blade with a slicing motion deep into its throat severing the jugular vein. The lion sprang back gushing blood over Harry as it did. Scrambling to his feet, now tightly holding his adapted (“Pipe Brand”) butchers knife in his hand he crouched forward, his right arm bleeding profusely hang limply. Staring at one another, Harry caught a wild glint in the lions eyes from the starlight. Not a moments hesitation, back on his feet, Harry decided it was his turn to roar and roar he did, using every kind of abusive language he could think of, he let it out as loud as he could, in an effort to drive the lion back. The lion must have seen the rage in Harry’s eyes and backed off, slinking into the darkness – himself now losing a lot of blood and in obvious pain. Lions at night are the most vicious creatures ever to confront.

Anticipating the other lions’ return, Harry finding a suitable tree and with one arm immediately fought his way up to as higher branch as he could muster, (later measured to be 12 feet) then strapping himself to a branch with his belt, in case he passed out from loss of blood. As expected, it was not long before the other lion showed up, with his dog Bull still snapping at its heels. The lion, smelling blood and seeing Harry in the tree, tried to climb up but (Bull man’s best friend) knowing Harry was in the tree kept the lion occupied from behind. While this was happening, he heard the jangling of tin pots, a short way off carried by his one ranger. In desperate need of water, he asked him for water but he had none. He told him to tree himself and keep out of sight from the lion. Then shortly after this with his police/ranger up in a tree, he heard more clanging. Those were they that hang around the pack donkeys’ necks and knowing they were his, he shouted to his rangers to fire shots to frighten off the menacing lion.

After Harry’s rescue by his police/rangers, he sent one to find water. They were still eight miles from camp with the other lion following all the way, also hoping for a crack at him. Meanwhile, his horse had made it back alive and it was he who had alerted the rangers. Harry had hit the mark. The lion Harry stabbed, died a short while later with two holes in the heart as discovered by the rangers who skinned the lion for Harry’s trophy the next day. Yet for Harry a new chapter of survival had just begun, which no lion attack survivor should have to endure. With a high fever, in great pain and permanently thirsty, it took five days for four bearers carrying water for Harry and using a machilato (type of stretcher) to get Harry to Komatipoort. There he was accompanied by a friend W. Dickson (from Steinaecker’s Horse war days) by train to Barberton hospital up in the mountains on the Swaziland border.

No pain killers or treatment to any of his wounds. Harry had traveled 193 km (120 miles on foot) through wild bush all the way from M’timba to Komatipoort by bearers on a machilato, then for 120 km (70 miles) by train to Barberton. Bitten in the shoulder and dragged 94 yards, torn by lion claws, lacerated by rocks and with severed tendons in his right wrist, he could not eat but drank gallons of water. His shoulder stank so much he had to face the other way to breath. Rotting and full of blood poisoning and yet still alive, Harry arrived at the entrance to the Hospital. An unrecognizable mess was carried into the Barberton outpost hospital and to the hospital staffs amazement he lived. Putting it his way; “I remained on my back for many weeks, and at one period the doctor despaired for my life.” Being the survivor Harry was, he not only lived, he served another 44 years as a ranger serving the Kruger National Park until his retirement in 1946, to the town of White River, where he died in 1964, at the ripe old age of 87, two weeks shy of his 88 birthday.

In December 1902, came Thomas Duke – native name M’Xhosa, a language he spoke having come from the Cape Coastal region – to be stationed at Lower Sabi. In May 1903, Cecil Richard de Laporte joined the other two and was stationed at Kaapmuiden. It must be said that Gaza Gray – native name M’stulela – was the first game ranger of the park but he was in fact under a private arrangement with the park and therefore unpaid. In mid-1902 he had requested the warden to act as an honorary ranger and be paid in grazing for his cattle; in so doing, he was never considered employed as a ranger for the record. He ran the eastern part of the reserve between the Sabi and Crocodile Rivers from the Selati Line to the Mozambique border in the south. A substantial area to patrol on horseback.

Then in May 1903, adjoining the northern boundary of the Sabi Reserve along the Sabi River, the Shingwedzi Game Reserve was proclaimed. This new reserve was to form the northern part of the Kruger National Park, situated above the Sabi, all the way to the Limpopo River. Warden Stevenson-Hamilton was appointed to administer this new game reserve as well, to his great joy; considering he was largely instrumental in getting it proclaimed in the first place. It took four months of preparation before he had the pack donkey’s and supplies he needed to inspect, which happened during September and October of 1903. Although finding it scarce of game, he considered it ‘well worth protecting’ for the future.

Sabi Reserve Trolley with Game Ranger Thomas Duke and Stevenson-Hamilton’s Staff. This is the Second Rail Trolley Called the “Passenger Trolley”

New Beginnings with a Great Future

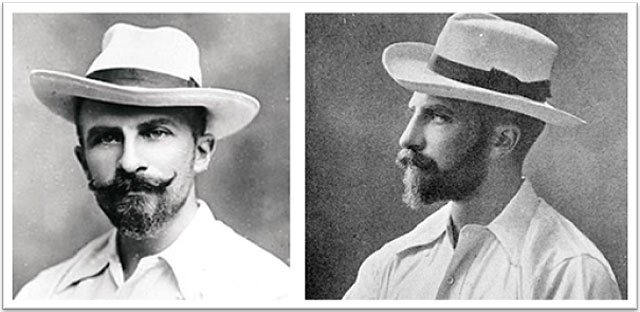

Some background of the warden to understand him better. Major James Stevenson-Hamilton was a Scot, although born in Dublin, Ireland on 2 October 1867. He came to South Africa from Scotland in 1888, where he served in the 6th Innis Killing Dragoons, stationed in Natal, educated at Rugby and the military academy of Sandhurst. After a short stint in South Africa, he left the military in 1898 to explore more of the continent. His explorations took him as far as the Kariba Gorge by boat and later Barotseland on foot, then trekked across Northern Rhodesia to the Kafue River. In 1899 he returned to Natal and the British military, to fight in the Anglo-Boer War (where he became a Major in 1900) until 1901.

Stevenson-Hamilton was an independently wealthy man, owning large family estates near Glasgow. He spoke neither Dutch nor any African languages and yet Sir Godfrey Lagden, Commissioner of Native Affairs (stationed in Pretoria) in charge of the Sabi Game Reserve project, saw in this man the qualities needed to make a success of this new, National Game Reserve, he was hoping to establish in the Transvaal. Lagden’s position changed in July 1905, when Native Affairs was relieved of its appointment of the Sabi Game Reserve, which was then transferred to the Colonial Secretary’s Office. The warden and maybe the entire Kruger National Park had been very fortunate to have had Sir Godfrey for those three short years, in which the reserve had become established and set up.

Well, if anyone said Stevenson-Hamilton was wrong for the job, were in for a huge surprise. For one to say that hostilities, political and otherwise, were not a problem for this man, would have had to be grossly ignorant. This short, astute yet forceful man, has to go down on record as being one of the toughest, kindest, most comprehensive and accomplished men in all of Southern Africa’s history. Never mind what conservation owes to him.

Against All Odds

Digressing a little and considering all the odds Stevenson-Hamilton faced for the cause of nature, I cannot think of anyone (and I hope you will agree) more accomplished in what he did for the Kruger National Park and wildlife in general, than any other man. Fortunately for us, he set the high bar that needed to be reached, because that bar has been steadily coming down ever since.

A short bit of history here. In 1902, seeking a civilian post after the Anglo-Boer War, Stevenson-Hamilton applied for the job of game ranger for the Sabi Game Reserve and was commissioned as warden on July 1st of that year. Although the peace treaty had been signed, the reserve and in fact, the entire region was still under martial law with Col. Steinaecker, a mean spirited man, full of strife and breathing fire, his corps still in charge, gave the new warden many troubles. Except for WW1, and a short time after his service in that war and even though he had his own wealth to fall back on, Stevenson-Hamilton through major odds, continued as an active civil servant at low pay for the sake of nature and its preservation, until his retirement from the Kruger National Park in 1946, to settle on his farm near White River.

See you for our next Selati Line adventure: ‘A Walk in the Park’