Selati Line – Part III

Selati Line – Part 3

War, Komatipoort to Sabi Bridge

Make Your Own History, if There’s None to be Had

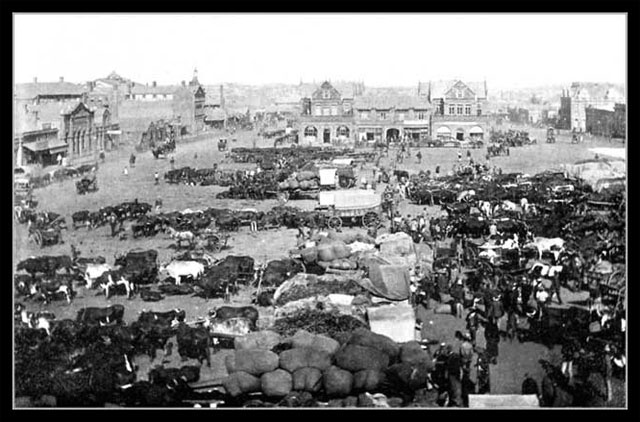

Digressing a little, it is worth knowing, that at this time in England, a four-pound loaf of bread cost 5d. or 6d.; yet in the Transvaal, bread cost four times more, at 6d. per pound (that’s when bread weighed more than a pound). The market-place in Johannesburg received approximately two hundred wagons a day, mostly drawn by twenty oxen each, with loads of 7000 – 8000 lbs. (3.5 to 4 tons) per wagon. The reason for all these wagons is that everything had to be imported and some foodstuffs and livestock like donkeys, came from as far as South America. The ports used at this time were those controlled by the British, namely Durban and Cape Town and both these lines never reached all the way to the goldfields. Can you imagine the mess on a rainy day! No wonder a railway line was needed by the Transvaal Republic and fast too.

The viability of the so-called Selati Goldfields had never been correctly established and their prosperity turned out to be very questionable! In fact, so questionable that there was no viable gold to speak of at all. In addition to this small problem, was the fact that this Selati Line, as I mentioned before, had now obtained the unenviable reputation of being one of the most expensive railway lines mile-for-mile ever built, having only covered the short distance of 80 km (50 miles). Not yet reaching it’s destination to mine in the first place.

The Oppenheim brothers ceased to pay the contractors when news of the Selati Goldfields non-viability became public knowledge, because the Transvaal Government revoked their concession. And at a time when the contractors were busy constructing the ‘Sabi Bridge’. At this stage, the bridge was at foundation level and its piers barely showed above the low waterline.

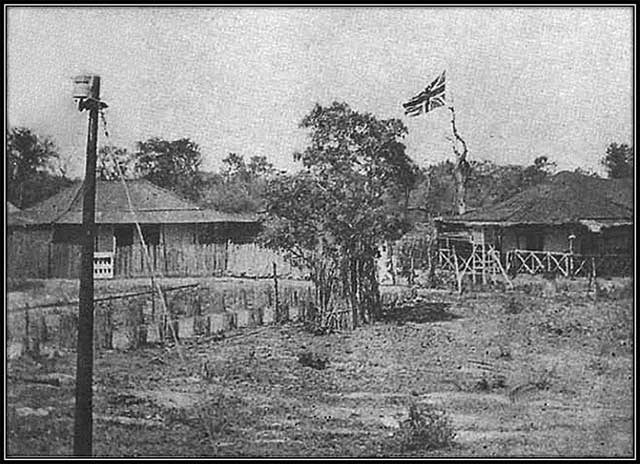

After tools were downed all along the track, the Selati Line was left unattended for 7-8 years, until the latter half of the second Anglo-Boer War, between 1898-1902 when a kind of military blockhouse was built, at what was then to be known as ‘Sabi Bridge’ and occupied by the extremely secret British forces (inside the Boer Republic), known as Steinaecker’s horse. You will read more about them later. (For the record, the picture below was taken a short while after Warden Stevenson-Hamilton of the Sabi Game Reserve moved into Sabi Bridge and made the buildings his headquarters.)

“Pots de vin.” That’s All! Why the Fuss?

The world took notice when Belgium calls the Oppenheim brothers before a tribunal of inquiry. At his tribunal, (the younger brother, who was the brains) Baron Eugene Oppenheim revealed a list of names showing that he paid “£30,000 Pounds to different members of the Executive Council and the Volksraad of the Transvaal Republic”.

This fact was presented when the tribunal questioned why the Selati Line cost £9,600 per mile instead of the regular £7,200 per mile. Baron Eugene Oppenheim explained that he had to pay out £2,400 a mile in bribes to the Transvaal legislature, which was thereafter euphemistically termed – pots de vin – in the proceedings that followed. At this point, Oppenheim presented a list of all the gifts and payments and to whom they were made or paid. “These payments,” he said, “were made to the Volksraad members to secure the concession.” The President of the Transvaal Republic, Paul Kruger (6,000 miles away) was also summonsed to appear before the Belgium court. When questioned, Kruger responded, saying that “he sees no harm in everyone receiving some payment as long as it does not amount to bribery.” Well I mean, can anyone credit that? And no one did!

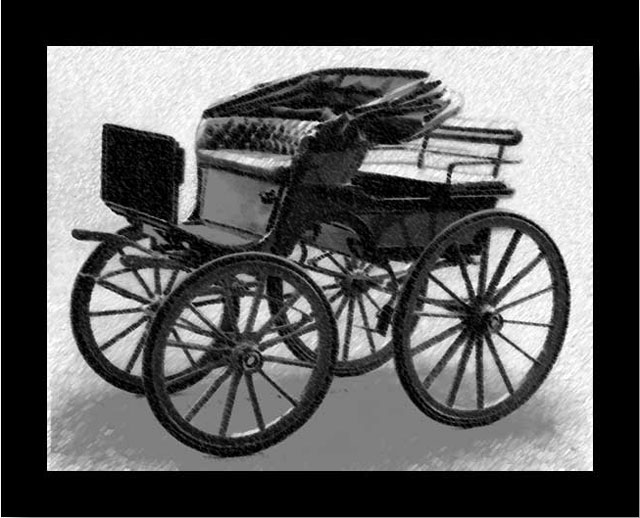

I will not go into the list or give details, since this history is readily available from newspaper archives and law journals, but I will tell you that the general list involved cash, gold watches, horse buggies (spiders) and the like, amounting to a very large sum of money.

Can you Make an Honest Buck and Stay Alive?

Of a greater cost than the lines’ financial loss, was that of the shareholders, (who called for the case against the company) and cost in lives for the families of the workers on the Selati Line. So great was the price paid for such a small, failed project that one could consider it almost immeasurable. To compare this with similar projects of today, the following accounts would be unprecedented anywhere in the world and would cause an international incident, to say the least.

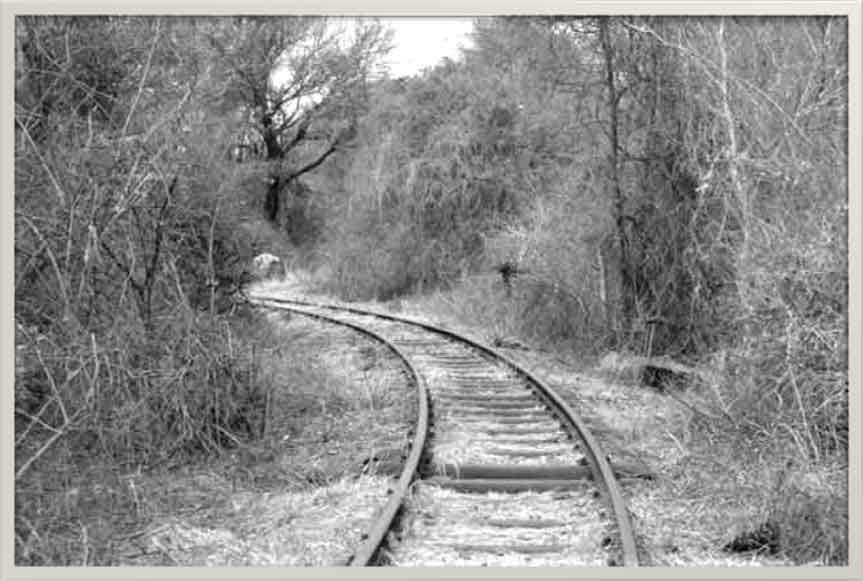

History records, that the stats given by the contractors were said to be a life for every sleeper laid from Komatipoort to Sabi Bridge and this figure has been touted from then until now by many sources. Considering that it was claimed, it has to be accepted or rejected. Let’s check it out. The entire 80 km (50 mile) trip on the Selati Line could be walked on metal sleepers from Komatipoort to the Sabi River, without stepping on the ground once, which puts the sleepers laid every meter (yard) apart (see image below on a narrow gauge line). That makes, according to my calculations, some 80,000 sleepers from Komatipoort to the Sabi Bridge.

Where Did All the People Come From?

The figures are statistically too high and I for one, can’t accept them. A staggering figure of 80,000 lives or thereabouts in one of the remotest areas of the world? This is the area Sir Percy Fitzpatrick, and many others, rode ox wagon transport only a few years before. He wrote the book ‘The Outspan’ published, 1897 and later, ‘Jock of the Bushveld,’ published in 1907 (he was knighted for service to the Queen). How about this quote, attributed to Fitzpatrick about the Selati Line; “conceived in iniquity, delivered in shame, died in disgrace.” It was said, who the fever never got, the lions hunted down. How many never took their pay home is anyone’s guess. One has to ask the question, ‘where did all the people come from?’ I can’t find direct data on this. For more than 80,000 people to die over such a short distance, makes no sense and where were they buried? The link to the sea and ships was down the track 100 km (60 miles or so) at Lorenzo Marques. In the town, there were doctors aplenty and ships doctors by the dozen, (some on shore and some at sea).

Consider that in December 1893, at around the same time, the British South Africa Company under Cecil Rhodes and Leander Starr Jameson killed 10,000 Ndebele in Matabele Land, Rhodesia (10,000 give or take a few carried away by lions, etc.). The figure of the wounded is not given. The Ndebele nation, then under its chief Lobengula is said to have been destroyed, (almost wiped out) after the death of some 10,000 warriors and here we are talking about 80,000 workers, in peace time!

I think these statistics need to be redressed. Even if that figure is halved, making one death for every two sleepers laid, the number is still an unacceptable 40,000 dead. The records of railway worker deaths in our next story, with a similar history and conditions as the Selati Line, says its more like the real thing to go by.

See you for our next adventure: Selati Line – Steinaecker’s Horse and War