Sable, A Respected Powerful Antelope

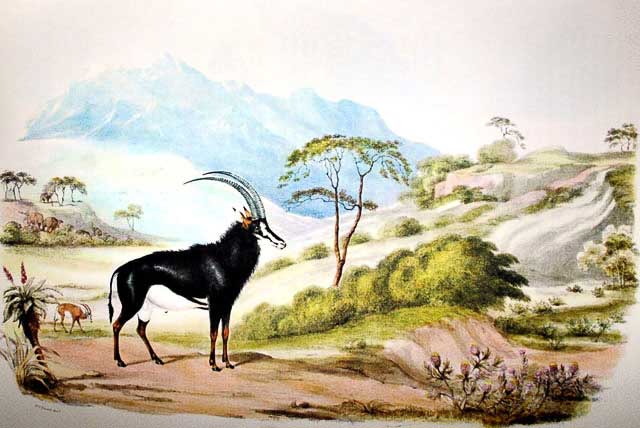

Sable Antelope Painted by William Cornwallis Harris from his 1838 book, ‘Portraits of the Game and Wild Animals of Southern Africa.’

Sable Antelope and Their Story by Cornwallis Harris

The Sable antelope (Hippotragus niger) was discovered in the Magaliesberg mountains on Tuesday 13th December 1836, by non-other than the famous early African conservationist, artist and explorer Sir William Cornwallis Harris. Harris was born in Kent England on 2nd April 1807 and after joining the army at the age of 14 was posted to India as an engineer at the age of 16, where he later also died of fever on 9th October 1848, aged 41. His full account of the Sable venture is laid out in the book Portraits of the Game and Wild Animals of Southern Africa, written by Harris himself and published in 1838.

In 1836, being ordered by the army to take two years off for convalescing in Cape Town, after contracting too many bouts of malaria while in service in India. Harris was there on duty as a military engineer, stationed in Bombay for the British East India Company. Not long after arriving in Cape Town, Harris set out for Grahamstown.

Grahamstown was a common place for expeditions to set out from, because all the best wagon builders, craftsmen, arms and ammunition, oxen, (salted) horses as well as leather-goods were there. Also, Grahamstown sported good hotels and boarding houses where traders hung out and regrouped after offloading their high priced wares.

Two big-game hunters and ivory traders Robert Schoon and David Hume from the 1817 Scottish settlers in South Africa. These two would end up being invaluable to Harris’ expeditions. Hume was a good friend of Mzilikazi, king of the Matabele kingdom where Harris was soon to go. In those days, it was imperative to get permission from the king of the region you intended to explore or shoot in. This favour was granted if you knew someone the king already knew and approved of and only if such a one should introduced you. Added to this, presents and favours given to the king were also in order.

Getting on With the Show

Robert Moffat, the famous missionary stationed at Kuruman and also David Livingstons father-in-law, was the next contact Harris became acquainted with. Moffat was on very good terms with king Mzilikazi, – Shaka’s foremost military leader, who with many other Zulu’s left Chaka and so started the Matabele nation – as well as other local chiefs and kings. Moffat’s introduction aided Harris, he, being taken care of throughout his mission to paint and acquire specimens for the Zoological Society of London and the British Museum as a field zoologist.

With wagons fully loaded, hunters, trackers, spare horses and oxen, Harris left Grahamstown in 1836 and set his sights for Kuruman, gathering specimens on his way. After his brief visit with Moffat he headed in the direction of the Cashan Mountains of the Magaliesberg region, because it was said to be good game country by none other than Robert Schoon, who knew it well. While tracking a wounded elephant, – a needed sample – Harris saw a pitch black antelope he had never seen or even heard of before. This encounter shook him so much that all he wanted to do was to get a specimen before they were lost to him, maybe forever, although he restrained himself from breaking off the elephant hunt right then and there, going back later in search of them. It’s interesting to note, that for many years the sable antelope was called the Harrisbuck. The following is Harris’ account of this chance meeting in his own words, slightly edited by me to make the English better understood for the modern reader.

A Hunt Like No Other

“Towards noon of this, the third day of tracking, having taken fresh horses we quickly came upon the hoof marks, this time the heard denoted its having divided into packs. Following the largest group of tracks, then cautiously peering over a rocky ridge, there I was greeted with a gratifying sight of two buck clad in their ‘black attire’ like chief mourners at a funeral, grazing by themselves in a stony valley some five or six hundred yards from us. I quickly withdrew my head and told my accomplices and the Hottentot trackers what I had seen. Although at last fortunately found, the quarry had yet to be secured. Two fresh caps were instantly applied to my trustworthy 10 bore, double barrel, – holding a quarter pound hardened lead ball per barrel – while the others followed suit with their rifles, although the Hottentots had to renew their damp priming and wipe their clumsy gun flints. One quick moment of grouping, sufficed to direct our forces, this way giving ourselves the best chance of intercepting the animals from a tangled maze of ravines, which ended in an impenetrable canyon. Deciding upon a simultaneous mounted attack from different angles, focusing on the handsomer of the two, the other being freed.

Bang, bang, bang – went the rifles and in an instant, with one unfortunate hind leg dangling from the hip, the cripple dashed into a scrub of flowering proteas, above the blossoms of which, his sweeping horns alone were visible. Pressing him on horseback through the corpse, he broke within a few yards from me, when another shot through his body laid him sprawling on his black side. Quickly recovering himself, however, he was again on his feet and before anyone had reloaded, was making the best of his good fortune heading directly toward the canyon at the neck of the valley. Aware that if he once gained this concealment, he was lost to me and my heirs forever – without waiting to drive the bullets down my rifle, I sprang into the saddle and exhorting Andries to follow on his horse instead of stopping to reload, I heaved in the spurs to my steed and dashed after the fugitive. I have before remarked that the genus antelope should have been created with three rather than four legs, inasmuch as they invariably appear to run faster upon the odd, than upon the even number; and here indeed was a case in point.

Interestingly, upon the first discovery of the herd on the morning of the 13th , I had made my way into the middle of them almost without an effort, it was now with the utmost difficulty that I could even keep abreast of them. Swinging his tasseled tail from side to side without one symptom of distress and squinting at me occasionally over his swarthy shoulder, as if to say; ‘Pray catch, if you can’, the wounded quarry rattled gallantly along over broken ground, beset with buffalo holes and strewn with pointed stones. Fast gaining the jungle he appeared to be gaining heart also, as each stride brought him nearer and nearer to his citadel; but at the termination of a mile, when close to home, a yawning ravine arresting his forward dash for freedom, he was compelled to swerve. During the progress of the chase to this point, my sorrel Gallaway had twice kissed the ground, but twice clearly recovered himself, after I had prepared myself for a severe fall. With one single bound he brought me clearly within range of the prize, only a might inferior to himself in stature, faced instantly about lowering his great horns and charged. Ramming down the ball as I retreated, I quickly came about facing him once again. Again he tilted at me and receiving both shots through the shoulder, was then overthrown and slain!

Some Descriptions Fail To Describe

Vain would it be to attempt a description of my excitement, when till now three days of toilsome tracking and feverish anxiety, unalleviated by almost any incident that could inspire confidence, or even hope of ultimate success. I finally found myself actually standing over the prostrate carcass of such a brilliant addition to the catalogue of game quadrupeds – so bright a jewel amid the riches of zoology! Turning it over and over, I thought I could never have scanned the prize sufficiently and my companion after extensively feasting his eyes in silence exclaimed, ‘the sable antelope would doubtless become the admiration of the world!’

I immediately made a portrait on the spot while the skin and head were removed and carried upon a pack-horse borne to the wagons. My last night in the bonny mountains of Cashan, were spent preparing the skin for the long journey that lay before us. Having been thoroughly salted, it was folded up and enclosed in an empty meal bag – a place being allotted to it at the foot of my bed, which it occupied for the greater portion of our return pilgrimage. A highly unenviable bed fellow and source of perpetual anxiety, it finally reached Cape Town in the state of the highest preservation; and having been elegantly made up by the taxidermist Monsieur Verreaux the French naturalist, it now graces the collection of the British Museum.”

On that first day, at first glimpse, Harris saw the similarity of the sable to the roan antelope (aigocerus equina). With this first known species, the sable is indeed recognised, being identified as (aigocerus niger). Today this species is known as (hipppotragus equinus and respectively hippotragus niger).

Written and recounted by Moz from Harris’ book.