Selati Line – Part VII

Selati Line – Part 7

When the Sun Went Down

Grace and Favour did Not Abound

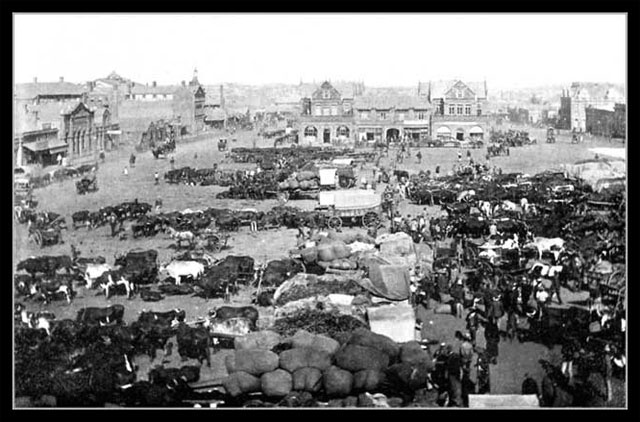

This was an era of pronounced wealth and prosperity, with no middle class to speak of, although the people were greatly divided down many lines, kindness and sharing was not part of the common people’s way.

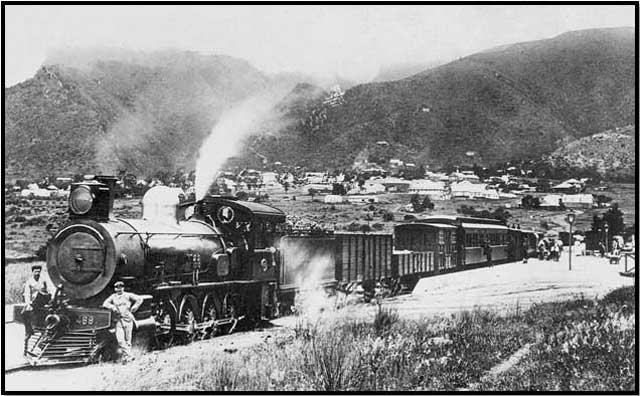

James Stevenson-Hamilton, reflecting on these times, wrote: “The line was now taken over by the South African Railways, and Sabi Bridge found itself served by one train a week each way, the hour on both occasions being about 2 a.m. For some inscrutable official reason, the siding and water tank for the engine had been placed on the other side of the river, amid uninhabited bush; while our side – the inhabited one – was not a scheduled stopping place. Thus, for some years we were dependent for the delivery of supplies, and the taking up, and setting down of passengers on the good nature of the guard of the train. If he did not happen to be in an amiable mood, he could, for instance, ‘deliver’ fifty bags of mealie meal in the bush a mile away across the Sabie, whence our only means of getting possession of it – unless the river was very low at the time – would be to bribe the ganger to bring it over on his trolley, an act on his part liable to get him into serious trouble if found out. Of course, as soon as the railway construction began, I had been obliged to hand over both my trusty trolleys, and now, with only one connection a week with Komatipoort (and that involving sitting up at the siding until 2 a.m. over a campfire) I felt that the coming of civilization had altered my lot for the worse.”

The reserve was saved for the time being and life carried on as best the warden could cope. For the next 13 years until 1926, things remained at one train service per week, both ways, although areas like Accornhoek, Hoedspruit, Letsetelli and Zaneen were developing fast and at a steady rate while road transport was becoming increasingly popular. In the meantime, this poor warden had to sit tight, ‘bite the bullet’ and wait out the years for better times.

Now Times They’re-a-Changin’

Things began to change fast by the years 1925/6; the government passed the National Parks Act in 1926. Stevenson-Hamilton compared the passing of the act to a “fairy-tale come true,” “for his Cinderella,” a term he regularly applied to the reserve, with great fondness. And so the Kruger National Park was established, becoming the first national park in South Africa, (and the second in Africa) and the first camps to be set up were, Skukuza Pretoriuskop and Satara.

At this time, South African Railways had almost taken over the Kruger Park and were responsible for transport, marketing, publicity and catering, as well as control of the take at the gates and shops. The Parks Board were paid a percentage for maintaining game rangers, attendants, roads and camps. An interesting fact is the law restricting passengers from going into aircraft pilots’ cockpit while in transit, began as an ordinance for locomotives.

A ‘Round in Nine’ Anybody?

Before the proclamation of the Kruger Park in 1926, income from the railways was so low in the Lowveld (pun not intended) at that time, that a radical approach was needed and an idea was born; which was to institute paying tours. It was suggested that tourism (going around – ism) in South Africa be created, long before the advent of tour buses. Johannesburg to Lorenzo Marques and back became a good idea and so the “Round in Nine” came into existence in 1923. Believe it or not, the “Round in Nine” was a very clever and well laid out plan. Who thought of it, no one knows, but it consisted of a nine-day tour from Johannesburg via the picturesque Lowveld and (would you believe it) through the Kruger Park at night, – yes at night – and on to Lorenzo Marques by the sea, incorporating nine sightseeing stops on the way and if you can believe it, the park was not one of them!

But, go through the Kruger Park at night? Someone must have missed the bus or something. When the warden saw the itinerary, he was shocked. The trains were scheduled to pass through the reserve at night, without stopping never mind, because they never included it in the itinerary. A clever idea indeed, but missing the whole plot! Fortunately Stevenson-Hamilton knew the railway’s systems manager and suggested to him that at least, the trains should make the journey through the reserve in daylight, so he went to Pretoria to see him.

The following dialogue from the warden himself, in his book the South African Eden.

“But why?” the systems manager asked.

“Well,” said the warden, “perhaps some of the people might like to look at the game.”

The manager stared at the warden with a ‘look’, doubtful of the warden’s sanity, paused a moment, then looking more earnestly, he realized the man was serious and with that he threw his hands up, falling back into his chair in raucous laughter.

Then spurting out. “What! Look at your old Wildebeests! What on earth do you suppose anyone wants to see them for?”

“But look here…” – then suddenly, some kind of light went on somewhere.

And with that came the “I’ll make a bargain with you…” “I’ll only bring one rifle…” “It’ll amuse the passengers.…”

You know the stuff, heard it once, heard it too many times…

One lethal weapon employed from a train against unsuspecting semi-tame animals, what competitiveness!

Never mind the days. The wardens’ tact brought it down to one nights’ stop at the water tower, across from Sabi Bridge, fondly referred to as ‘Reserve,’ where the night stop involved dinner by a campfire while listening to the night sounds of the bush, until bed time on the stationary train. The next morning, – with no rifle, – on to Newington, – at that time still part of the reserve – which was further up the Selati Line and a stop there for one hour. And the tourists cried for more, more, more and the train stops became longer and longer and the rest, as they say is “history.” Bye, bye, railway officials.

This idea became so popular, that Kings to commoners worldwide, booked to do the trip and so ‘wildlife tourism’ was born on the Selati Line in Africa. King George of Greece, while departing after a brief stay in the reserve and lagging back a little, remarked “rather plaintively” to the warden who was accompanying him to the train, “Can’t you hide me behind a bush till the train has gone.” The warden’s remark about this incident was; ‘I really believe he wished it could have been possible.’

This new direction by the SAR promulgated at first, two trains a week and then there were three and then, yes you guessed it, special trains were supplied for ‘game tours’ to the park (“money, money, money, it’s a rich man’s world”). Then came the great depression in 1929, with a sting in its tail; no more tourism! (Ag-nee!) It was at this stage the S.A.R introduced combination trains to the Kruger Park; passenger and goods coaches mixed per train to save money. But tourism never died.

Next, was the era of the motor car? This idea actually started in 1927 and to begin with never really took off, having three cars for the year; at a cost of £1.00 per person, with bad roads and poor accommodation. But, as the facilities improved, the figure increased to 180 cars for 1928, steadily growing ‘til 26,000 people visited the park in around 1936. And as conditions continued to advance, so did tourism to the Kruger Park, until 2014, around 1.4 million people visited the park of humble beginnings.

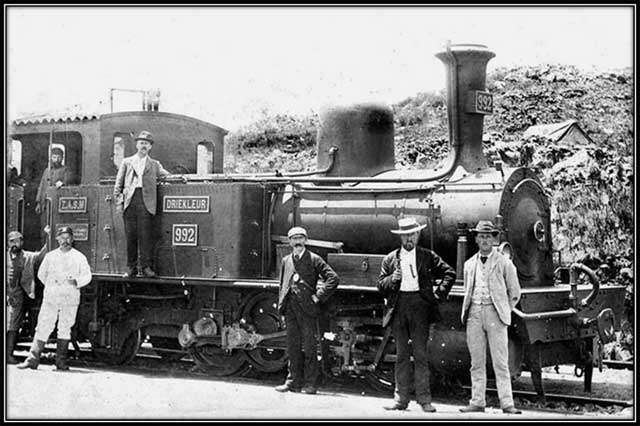

Then the Selati Line became no more

As the surrounding areas developed, so did the transport through the Kruger by train, to the extent of several trains per day and this on a single line railway track! Transport was required for agricultural goods outside the reserve, in the form of livestock, sub-tropical fruit, vegetables and sugar cane – ‘Selati’ sugar in fact – exploded; also, mining for iron ore, vermiculite, platinum, copper, rock phosphate and many more were opened up north, until this part of South Africa began to develop into a metropolis on a single line railway track? Something had to give.

Probably the saddest moment of the Selati Lines’ history was the collision of two trains between Crocodile Bridge and Skukuza camp, on New Year’s Day of 1968. The death toll came to fourteen, with thirty-eight seriously injured. This put an end to the Selati Line through the Kruger National Park forever. Resulting in the building of a new line along its western boundary, which today runs from Komatipoort up along the Crocodile River, – Kruger’s southern boundary – to Kaapmuiden. The new line going north from Kaapmuiden rejoined the old Selati Line a little after Newington on the other side of the Kruger’s north-western, boundary, leading on to Tzaneen and beyond.

The Selati Line through the Kruger National Park ended in 1973 and is now, no more, but the rail line on to the Selati River via the western boundary of the Kruger Park is still very much in service. Strange as it may seem and with an ironical twist, the Selati Line had become a major player in assisting Stevenson-Hamilton in the development of the Kruger National Park His – “Cinderella” – and now the huge 35,000 sq. km. Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park is the result. If the Selati Line had never existed, the outcome of the reserve would have been very different.

It is interesting to note, the Park’s administration centre is still situated at Skukuza, (old Sabi Bridge Camp) where the Selati Line first ended in 1894, until Steinaecker’s Horse set up the British block house there in 1900. I believe the Sabi Bridge over the Sabi river at Skukuza itself, should be a symbol and made a national monument to the Kruger National Park. There is no other like it in the whole country and its contributions to the South African economy and tourism cannot be equaled.

I know the beginning of this story is somewhat crammed full of facts and hard going, I beg an apology, although to fit the story for the Internet it had to be short. Writing the story has been fun, but hard work getting it all together without making it seem like an historical document. I hope you enjoyed it and I am pleased there is now a document, which at least forms a framework of this epic time in history.

And so the sun went down on the Selati Line for the last time in 1973, but not before she had left an indelible mark, on all who knew her and lived by her.

Col. James Stevenson- Hamilton would be pleased to know that little “Cinderella” made it to the big time. The Selati Line, born in iniquity, veiled in suspicion, now concluded in prosperity.

Thank you for joining me in this seven-part adventure of the one time Selati Line.

Posted by Moz

References:

My thanks go first, to a friend, in the person of Hans Bornman. A man I greatly admire, not only for his accurate research, but also for telling stories of the Lowveld, alive in words. Without him, and his references, I would have told a poorer story. Thank you Hans.

- Pioneers of the Lowveld – Hans Bornman.

Secondly, since doing my research, I have come to identify much more with this warden’s contribution to the world of conservation, than I could have imagined. A friend indeed, I would have been very fortunate to have had.

- South African Eden – James Stevenson-Hamilton

If you love the Lowveld, it’s worth reading both books.

Acknowledgments:

Thirdly, thanks to my grandfather, Andrew Mauritz Mostert, who taught me much and told me many tales of the bush, including this one of the Selati Line. He himself was a pioneer of the Lowveld, in Nelspruit and the Timbavati reserve, and a founder of tourism into the Kruger National Park – from when it started, until the war years of 1939-45

To You the Reader

Thank you for reading this story through, because I know how much better you now understand the Lowveld and it’s people. I am sure it will have enriched your life as it did mine, the day I first heard it, from a gentle, but hardened, tough old bush man, who once survived a hand combat with a fully grown lioness for almost a whole hour before he was rescued. Suffering sixty three stitches in his head alone.

My Support Mechanism

Lastly, thanks to my wife, an accomplished writer and editor, who patiently sat through all my read-backs to edit my mistakes, without having to change my voice – too much.